AlbumsRgood

I thought I?d turn something of yesterday?s lecture into a blog. For first-year song writing we were looking at some tracks from Don McGlashan and the Seven Sisters? latest album ?Marvellous Year?. It spawned a good discussion on the validity of albums and how they combine songs to communicate more than their constituent parts. In the title track Mr McGlashan sings to a comet. It might seem a ridiculous thing to do (it is inanimate and therefore can neither hear nor respond) but is a novel way of tackling the core issue at hand, namely the demise of the human species. The tactic, it seems to me, is to invite the audience to consider time on a scale vaster than one?s own lifetime. The lyric describes how in ancient times people would become fearful and offer prayers and sacrifices when the comet came around. This juxtaposes with the relative calm with which it is viewed now. The lyric then looks to the future visitation of the same comet and laments that a child should have been born to write another song to it (implying that no child will be born?that by then we will be extinct). In the interim McGlashan acts as apologist to the human race, listing our achievements in the past tense ("we had"), including everything from the lofty idealism of democracy to oppression and torture, with the mundane world of sport (rugby union and motor cross) and commerce (the Briscoe?s lady and Interflora) sandwiched in between (for the full effect you need to buy the album, the rhyming and disconcerting harmonic shifts underscore the bathetic juxtapositions to a treat). He asserts, however, that as a race we did the best that we could (and can do no better than destroying ourselves). In so doing he seems to posit a degree of limitation, that our inherent nature will doom us to failure in spite of our higher aspirations and indeed achievements.

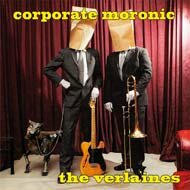

The ensuing track is about a radio programmer (its title). The protagonist frets about choosing the right song for radio play, prays for a sign from God to help him make the right decision. He loves his wife and family and obviously wants to prosper, keep his job with his pretty assistant in her little black dress. The riff underpinning it is a barely disguised reference to ?Born to be Wild? which merely helps point up the radio programmer?s inherent conservatism, his desire to be free of risk. At the same time the generic quality of the riff acknowledges that the imperative to sell things such as songs also acknowledges that people prefer the cosy warmth of the moronic rather than insightful musings on countless centuries, comets and extinction which has preceded it.

The communication lies between the songs as much as in them. The radio programmer lives in a time line of weeks or months (the lifespan of a hit song, after which a replacement must be found). He is engrossed in the zone of selling something in the here and now to preserve the status quo, his position, power and ability to provide for the wife and kids he loves. He has no time or use for thinking on the time scale of comets?not many people do. Between the two songs lies a perception of disinclination towards the uncomfortable big picture that the title track presents us with. It is discomforting on account of the insignificance we feel next to the vast swathes of time the comet inhabits but we don?t and so, it would seem, very few bother contemplating such matters.

The dialogue between the songs reveals the basis for McGlashan?s pessimism. We, as a species, need to think on the comet?s time scale if we are to save ourselves. But most are unwilling (or more charitably unable) to view themselves on this more cosmic time scale (in the hand-to-mouth world of family and mortgages most are too locked into survival month by month to ever get their heads up to see the wider picture). The demands of short-term survival are the very things that will kill us off.

So the title track posits a notion of human limitation, whilst ?Radio Programmer? presents us with a case study of the commercially driven (implied aesthetically valueless), gerbil-in-a-wheel type of human endeavour that will probably doom us. Either song is viable on it?s own, but together they create an experience where the sum is greater than the constituent parts. Viva l?album! Good work Don!

The ensuing track is about a radio programmer (its title). The protagonist frets about choosing the right song for radio play, prays for a sign from God to help him make the right decision. He loves his wife and family and obviously wants to prosper, keep his job with his pretty assistant in her little black dress. The riff underpinning it is a barely disguised reference to ?Born to be Wild? which merely helps point up the radio programmer?s inherent conservatism, his desire to be free of risk. At the same time the generic quality of the riff acknowledges that the imperative to sell things such as songs also acknowledges that people prefer the cosy warmth of the moronic rather than insightful musings on countless centuries, comets and extinction which has preceded it.

The communication lies between the songs as much as in them. The radio programmer lives in a time line of weeks or months (the lifespan of a hit song, after which a replacement must be found). He is engrossed in the zone of selling something in the here and now to preserve the status quo, his position, power and ability to provide for the wife and kids he loves. He has no time or use for thinking on the time scale of comets?not many people do. Between the two songs lies a perception of disinclination towards the uncomfortable big picture that the title track presents us with. It is discomforting on account of the insignificance we feel next to the vast swathes of time the comet inhabits but we don?t and so, it would seem, very few bother contemplating such matters.

The dialogue between the songs reveals the basis for McGlashan?s pessimism. We, as a species, need to think on the comet?s time scale if we are to save ourselves. But most are unwilling (or more charitably unable) to view themselves on this more cosmic time scale (in the hand-to-mouth world of family and mortgages most are too locked into survival month by month to ever get their heads up to see the wider picture). The demands of short-term survival are the very things that will kill us off.

So the title track posits a notion of human limitation, whilst ?Radio Programmer? presents us with a case study of the commercially driven (implied aesthetically valueless), gerbil-in-a-wheel type of human endeavour that will probably doom us. Either song is viable on it?s own, but together they create an experience where the sum is greater than the constituent parts. Viva l?album! Good work Don!